“Alewife” is a personal, biological and historical account of the alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), one of the (formerly) most abundant sea-run fish of the U.S. Atlantic seaboard. It is the only full-length treatment of the natural and cultural history of this keystone wildlife species ever written.

The newly published book is written by Doug Watts of Augusta, with contributions by his brother Tim Watts and his father Allan Watts, who is now deceased. It is the product of 12 years of historic documentary research, much of it done at the Maine Archives in Augusta, Maine, on the troubled history of sea-run fish and dams in Maine and New England. Many of the historic documents in the book are published for the first time since they were written.

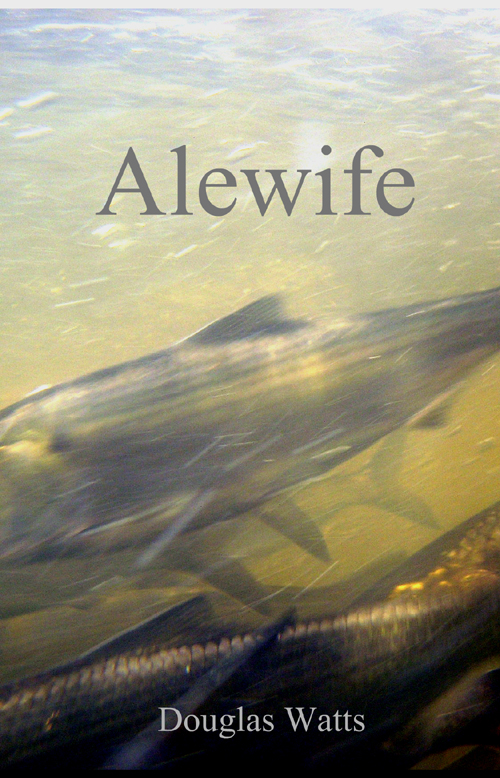

The front cover features an underwater photograph of native alewives, blueback herring and American shad ascending Presumpscot Falls on the Presumpscot River in Falmouth in June 2006 — an event solely due to the removal of the Smelt Hill Dam at the river’s head of tide in 2002. The book’s chapter on the Presumpscot River (‘The Alewife Who Went to the Supreme Court’) is drawn from historic research conducted by Friends of the Sebago Lake on the earliest history of the Presumpscot River and Sebago Lake at the Maine Archives and the Maine Legislative Law Library. FOSL member Roger Wheeler and his students at the Mollyockett Middle School in Fryeburg contributed additional key early 1800s documents.

“Alewife” tells the story of a fish, the alewife, once ubiquitous to the eastern U.S., which is almost gone due to wholly human causes; and a never-been-told 400 year history of many long forgotten people who labored mightily to bring the alewife back. It tells the story of the fish through its own eyes and life, apart from what it ‘can do’ for us. It depicts a place where cultural, natural, political and legal forces wildly collide. It’s about the fight for, against, and over a dimunitive but once extremely abundant fish that still continues today in state and federal court rooms across the states of the eastern seaboard. It is about what nature in our backyards meant to us in the past, what it means today and what it might mean to us 10, 20 or 50 years from now. It’s a story about a lot of disparate people over 400 years and how nature and culture provoked them for good, bad and indifferent. It’s not nearly complete, there are many stories still untold, but gives a flavor for the battlefield, the stakes to be lost and gained and hints to where the tipping points have been and still are. It’s a hybrid, with all the advantages and disadvantages an unorthodox approach entails. Bridging gaps might be its central theme. I wrote this for an adventurous reader who is not afraid to skip a chapter and then come back to it later. It is intentionally kaleidoscopic; a multi-levelled story. The essays owe much to the series of young adult books, “Tell Me Why,” by Arkady Leokum.

The book is in two sections. One section is selected verbatim public domain record excerpts describing the species and its use and abuse by humans in New England from the 1600s to present. Most of these documents were written in quill pen, discovered and hand copied by the author, and have never seen the light of day before. The second section tells, in a personal essay style, the story of the alewife, based mostly on recent efforts in New England to protect and save them.

The book began several years ago as the historic texts with a short introduction and was originally intended for dissemination to fisheries scientists, environmental regulators and river conservationists as a technical, factual resource. At the instigation of a fellow writer, Kerry Hardy (who wrote the foreword), I loosened up to tell in a first-person voice my many encounters with these critters in the waters of New England since childhood and the obstacles one encounters trying to help them not go extinct. It’s a tough racket. These personal stories echo back to the historical texts, which detail how people 50, 100, 200 years ago tried to do the same thing and encountered nearly identical obstacles, albeit time-shifted by a century or three.

The tone and weight of the text is balanced to make it accessible to an informed and inquisitive lay audience and to a professional scientific audience; and above all, to be fully scientifically sourced. My brother and I’s personal travails trying to help alewives survive are deliberately told in a ‘camp-fire’ fashion and with the level of humor and absurdity the details deserve.